With the growing demand for emergency veterinary services, understanding the principles and techniques of triage is vital for veterinarians looking to excel in this specialized field. We will explore the various factors that come into play during the triage process. We’ll discuss the initial assessment of patients, including vital signs, history taking, and physical examination. And lastly, we’ll delve into the importance of rapid decision-making and effective communication among the veterinary team.

What is triage in the veterinary clinic?

Veterinary emergency triage is a systematic approach used to assess, categorise, and prioritise patients based on the severity of their conditions. It ensures that the most critical cases receive immediate attention and care, optimising outcomes and saving lives. In a traditional sense, triage has been defined as “the evaluation and allocation of treatment to patients according to a system of priorities designed to maximize the number of survivors.”

- Pre-hospital telephone triage

- Waiting room/Initial triage

- Primary survey and lifesaving interventions

- Secondary survey and diagnostic/treatment plan

If all of the above steps are performed calmly and accurately, an effective veterinary team should be able to anticipate and prevent emergency problems from worsening. So where does this often begin? As you’re about to find out, triage can start before the patient even enters steps foot in your clinic.

Telephone Triage

In the majority of emergency situations, owners will call the veterinary clinic prior to arrival. This often presents our first opportunity to gain valuable information and to calm and direct our client. Reception teams should be trained so that they feel comfortable performing telephone triage or be able to pass the phone to an appropriate member of staff to perform triage if necessary.

Contact information, including a phone number for the client and patient signalment, should always be obtained during our first interactions with owners and before clients are put on hold for transfer. The member of staff performing the telephone triage should have enough medical knowledge to be able to identify true emergencies and be able to direct phone calls to trained veterinary technicians or veterinarians as appropriate.

What are some questions for veterinary emergency triage?

- Is the animal having difficulties breathing?

- Is the animal conscious and able to move/ambulate?

- Does the animal have any bleeding wounds or obvious fractures?

- What is the brief nature of the emergency and time frame during which it occurred?

- Do the owners know how to get to the clinic and when will they arrive?

In true class 1 catastrophic emergencies where owners are concerned their animal has died or is dying, a resuscitation status (CPR/DNR) should be obtained if possible. Clients should also be warned that stressed or painful animals should be approached cautiously in order to avoid harm to the client.

Telephone triage is also our first opportunity to prevent further harm. Clients should be given appropriate medical advice by a trained veterinary professional in order to transport their animals in the safest possible way to the clinic (e.g., protecting the spine by lifting the patient on a hard board in trauma cases, applying counter pressure to haemorrhage, minimal restraint in dyspneic patients etc.).

Initial Veterinary Emergency Triage Examination

In the majority of veterinary clinics, the initial triage examination will be performed by a qualified veterinary technician or veterinarian. This initial examination should be performed promptly so that any necessary emergency treatment is not delayed. The initial assessment should include a brief succinct history during which the primary complaint is identified and an examination of vital parameters with the four key body systems assessed:

- Respiratory – respiratory rate and effort, respiratory noise, identification of open mouth breathing, increased/dull lung sounds, mucous membrane colour and CRT, oxygen dependency if necessary.

- Cardiovascular – mucous membranes and CRT, heart rate and rhythm, pulse quality and synchronicity.

- Neurological – level of consciousness, recent/ongoing seizure activity, ability to ambulate.

- Renal – assessment of bladder size and turgidity.

Severe dysfunction of any of the above systems can be life-threatening and so these patients warrant being prioritized and provided immediate veterinary intervention. Other priority patients may include patients with severe pain, recent toxin ingestion, trauma cases, dystocia, severe burns and hypo/hyperthermia due to their impact on the above body systems.

Client Communication

Communication of the findings of the initial triage examination is of the utmost importance. We must always remember that our clients have deemed the situation they are presenting for as an emergency, and so we must be aware that they will be stressed and anxious about the situation.

As such, if it is deemed necessary that the patient is brought straight to the treatment area and away from the owner, we should explain why we have made this decision. This is vital to ensure that clients are well informed and, if appropriate, report back regularly until they are able to discuss the case in more detail with a veterinarian.

Triage Station

In all clinics, it is recommended that there is a designated emergency station/room where basic interventional equipment and emergency drugs are easily accessed. This is often referred to as a “triage station”. Every new member of staff should familiarize themselves with the triage station so that when necessary equipment can be quickly accessed and reduce the chaos of emergency triage situations.

Primary Survey – A Thorough Triage Assessment

The primary survey is dynamic and ideally multiple steps will be performed at once (e.g., IV access by a technician while the veterinarian performs clinical examination). Additionally, oxygen supplementation should be provided throughout in any critical patient regardless of respiratory status.

What are the steps of a primary survey during triage?

- ABC examination – Airway, Breathing, Circulation

- Emergency database – electrolytes, blood glucose, PCV/TS +/- blood gas and lactate

- Emergent imaging – abdominal/thoracic POCUS, right lateral radiograph in suspect GDV, ecg

- Establishment of IV access

- Emergent treatments/interventions – IV fluid boluses, thoracentesis, CPR, dextrose, furosemide, epinephrine etc.

The veterinarian should communicate their clinical examination findings alongside their initial orders effectively to the rest of the team and these should be clearly documented (medication dose, route, time) to avoid mistakes and for future reference.

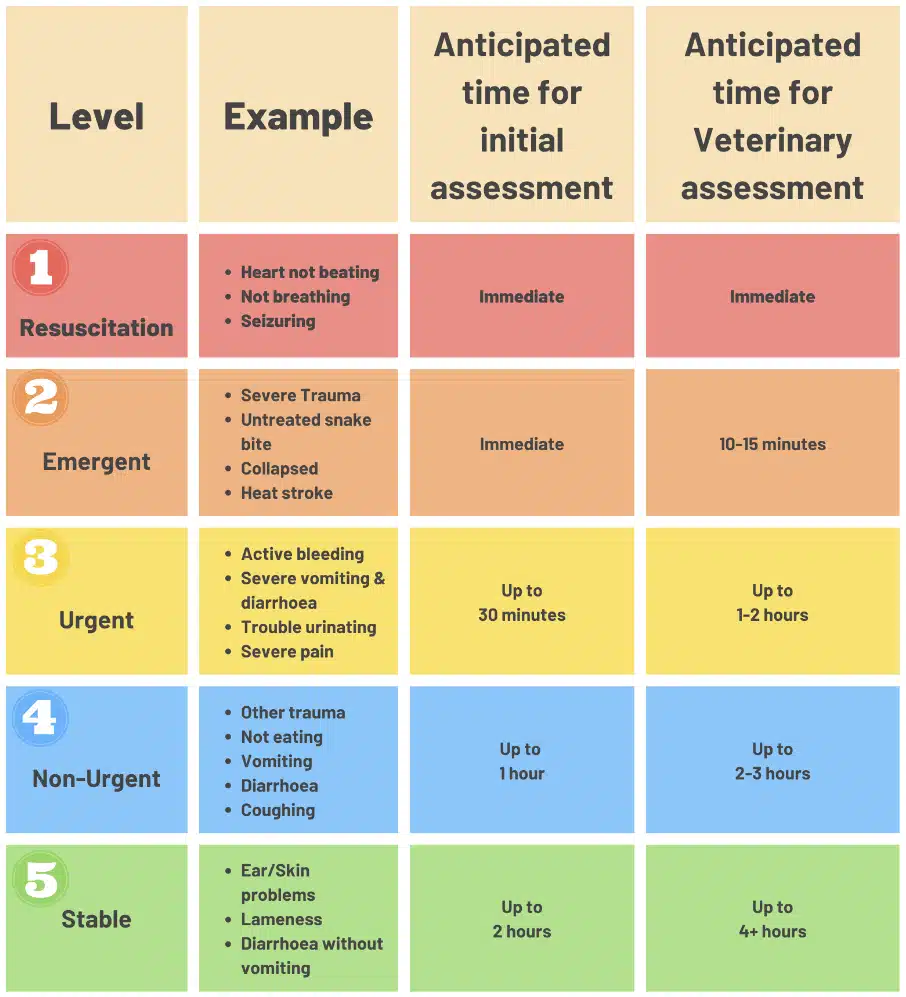

A clearly visible triage chart in the waiting room is the perfect way to inform clients (Source: PVE, 2022).

The ABCs of Veterinary Emergency Triage

A – Airway

The patency of the airway should be immediately assessed. If the airway is not patent, then intubation or emergency tracheostomy (if intubation is not possible) should be performed ASAP. If patency is affected by upper airway disease (such as in brachycephalic dogs/laryngeal paralysis), light sedation (butorphanol +/- benzodiazepines) may drastically improve the patient’s ability to breathe. Oxygen supplementation with flow-by oxygen should be provided throughout all emergency triages.

B – Breathing

The pattern of respiration should be observed before and during auscultation of the thoracic cavity. If the lung sounds are dull and a pneumothorax/pleural effusion is suspected, thoracic POCUS (point-of-care ultrasound) should be utilized if available to help to direct thoracentesis. If there is a high clinical suspicion that the pleural space requires decompression (with or without POCUS) in a severely dyspneic patient, diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed.

If any thoracic communication is identified, a seal should be made as soon as possible. Assessment of breathing can be aided by objective measures such as pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis. Breathing patterns will often be affected by pain and so in patients with a high suspicion of pain treatment of this with a fast-acting opioid such as fentanyl, methadone or hydromorphone may be indicated.

C – Circulation

Circulation is best assessed with a combination of hands-on clinical examination alongside objective measurements such as blood lactate, blood gas analysis, and doppler blood flow monitoring. The following should also be assessed to evaluate a patient’s circulation:

- Mucous membrane colour,

- Capillary refill time

- Temperature

- Blood pressure

- Cardiac auscultation for murmurs and arrhythmias

- Palpation of the pulses for quality and synchronicity

- Level of consciousness

Haemorrhage should be counter-pressured to prevent worsening circulatory status. If circulation is assessed to be inadequate, it is likely that the patient is in a form of shock and therefore, with the exception of cardiogenic shock, immediate fluid resuscitation should be performed.

Vital Diagnostics for Emergency Triage

In such a time-sensitive situation when faced with a critical patient, obtaining as much useful diagnostic information in as short a time span as possible can be incredibly valuable. This can quickly be achieved through several simple and swift blood tests. The following use only a small volume of blood but can provide large volumes of quickly and easily available information to aid the triage process:

- Blood Glucose

- Hypoglycemia can rapidly progress to seizures and death. Emergent treatment with 0.5-1ml/kg 50% dextrose bolus diluted 1:4 is appropriate in most situations. Conversely, hyperglycemia may indicate the need for blood ketones to be monitored.

- PCV/TS

- PCV increased + TS increased = dehydration

- PCV normal + TS increased = anaemia with dehydration, hyperglobulinaemia

- PCV normal + TS decreased = acute haemorrhage, hypoalbuminaemia

- PCV decreased + TS normal = haemolytic anaemia, non-regenerative anaemia

- PCV decreased + TS decreased = haemorrhage, anaemia and hypoproteinaemia in combination

- Blood Lactate

- Can be used to help localize poor perfusion by comparing systemic and localized results.

- Acid-Base Status and Electrolytes

- Electrolyte disorders can be acutely life-threatening. These should be assessed in all emergency patients to direct the acute and ongoing treatment plan.

- Platelet Count

Emergency Diagnostic Imaging

Point of Care Ultrasound is a quick and easy diagnostic test often used during triage situations. POCUS has many uses in the triage setting but the most important use is the identification of free fluid in the abdomen, pleural place or pericardial sac. Additionally, in any suspect GDV patient, a right lateral abdominal radiograph should be performed as soon as possible.

Secondary Survey

After a primary survey and immediate lifesaving interventions are performed, the secondary survey should begin. The secondary survey expands further on the initial triage and primary survey process and can be much more detailed and time-consuming.

During the secondary survey, a full clinical examination should be performed as well as a full history taken and discussions with the owner of the animal regarding primary survey findings and recommended next steps. It is during the secondary survey that more time-consuming diagnostics should be performed (e.g., further imaging and extended blood panels).

The triage process is dynamic and involves multiple members of staff within the veterinary clinic. Triage should be a large part of all new members of staff’s training so that everyone is prepared and able to assist in the process. This minimizes stress for the patient, the owner and all of the staff members involved. Patient and staff safety should not be forgotten as in stressful emergency triages this is often where veterinary professionals lose sight of their own safety.

Crucially, a healthy working environment where all members of the team feel comfortable asking for assistance and where good communication between staff members and owners is achieved will improve the triage process immensely. So to ensure a smooth triage flow in your clinic, download our full triage guide that you can quickly refer to in your next emergency situation.